This #Take5 is brought to you from Joy Igiebor a Learning Development Tutor within the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London. This is especially for the newbie LDer who feels a bit lost… who thinks that everybody else knows exactly how to ‘do’ Learning Development whilst they alone are thrashing about in the dark. Joy offers very helpful guidelines on workshops and tutorials – a beginner’s guide to Learning Development. Next week we have a post from the team at MMU – what the learning developer needs to know next.

A one – two – three of LD

I am now almost five years into my career as a learning development tutor (LD) at a University of London institution; however, particularly in the initial years of my role, I found that I had to do a lot of ‘rummaging’ to find advice specifically targeted at new and early career LDs. Although there were a host of resources and support on the Association of Learning Developers in Higher Education (ALDinHE) website, I guess in those initial years I was really searching for ‘a step-by-step manual’ on how to do the job. I had so many questions at a time when I was just trying to find my feet e.g., How do I run effective tutorials? What is a workshop and what should students be doing in a workshop? What if a student asks me a question that I don’t know the answer to? What exactly is a learning development tutor? Imposter syndrome was real and, darn-it, I just couldn’t find that step-by-step manual. Perhaps I can now see with hindsight and some solid experience that this is because learning development is essentially about relationships; relationships between the student and you, between you and your colleagues, and so on and so on; and that, therefore, there is not necessarily a ‘one-size fits all manual’ or way of ‘doing the job’, pedagogically speaking.

Prior to working in higher education (HE), I’d been a teacher for over 12 years, and in those initial scary years as a ‘newly qualified teacher,’ there had been a wealth of information and “guidance” about how to ‘do the job’ “properly” (indeed, much of this was often bordering on prescriptive, similarly, perhaps, in style to Ms Trunchbull from Matilda). In contrast, as a new LD, it felt somewhat that I was having to flounder and find my own way, much like a fish out of water. So, I decided to write down some thoughts and tips in the hope that I might have a record of something possibly useful for others, like me, new to the role and wanting to do a good job.

The extracts in this blog are based on a pragmatic approach i.e., what I have found through experience works well, rather than theory. That is not to say that theory is not essential to our practice as learning developers, but the focus here is on ‘practical ideas’ that can be used to ‘hit the ground running’ rather than (albeit very important) theoretical discussion. Given the confines of a blog, I focus on providing ideas and tips for two of the main student-facing aspects new LDs are likely to encounter in the role; namely, tutorials and workshops. Whilst being ‘new’ or ‘early career’ is not necessarily easy to quantify, these ideas will likely be of most use to those within the first couple of years or so of their career.

What are workshops?

It is likely, as an early career LD, that much of your working time will be spent planning, designing, and delivering workshops. So, what exactly is a workshop, what are its purposes and what should be included in a ‘good’ workshop?

Prior to being a learning development tutor, I worked in teaching and had little to no experience of conducting workshops. Whilst workshops and teaching lessons are similar, in many respects; that is, the aim is to construct knowledge so that students leave the session having learnt something new; the emphasis in workshops is ‘work;’ that is, students should be doing most of the work and, therefore, an active rather than passive ‘chalk and talk’ approach is often preferable. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t any room for explanation, teaching, and perhaps space for being more didactic in some instances; just that, for it to be a ‘workshop’ in the true sense of the word, the majority of your workshop content shouldn’t be completely didactic. Indeed, workshops often ‘work’ best when students have opportunities for practice, interaction, and space for questioning and discussion.

Now, all this may sound rather daunting as a new learning development tutor, and you may be wondering where on earth to start with making engaging and effective workshops.

How can I structure a workshop?

Workshops can be both nerve-wracking but also exciting to teach as a new learning development tutor. Like a story, lesson, or a tutorial, a good workshop should have a clear beginning, middle and end. That’s not to say that you need to stick rigidly to what you’ve designed or planned as it’s important to allow for flexibility, if need be. When I started as a learning development tutor, I would often have a ‘verbatim script’ that I basically read from as I was petrified of not ‘doing it right’. However, the messiness of workshops has to be taken into account. Students will often respond in ways you don’t expect, technology will go awry, activities will take much shorter or much longer than planned. As you gain more experience, don’t be afraid to ‘go off script’ as this is often where the beauty, fun, and real learning takes place. As an aside, I still use notes from time-to-time, but now more so as a guide and a prompt rather than to read from verbatim.

However, all this being said, workshops should have clear learning aims and objectives and these should be shared with students at the start of each session and reviewed at the end. The structure of a workshop should run something like this; ‘This is what we are going to learn’, ‘Here we are learning it’, ‘This is what we learnt’. Aim to intersperse periods of you talking with an activity or task for students to complete – a good rule of thumb is that for every 10 to 15 minutes of talk time (when student attention span starts to decline!) students should then complete a task.

Tasks should be clearly related to the learning aims and objectives and, as far as possible, aim to encourage dialogue and some type of interaction between the students, each other, and you (this does not necessarily have to be spoken interaction, it could be through writing or, if online, in the chat or some type of interactive tool such as Mentimeter or Padlet). When concluding a workshop, it can be helpful to review what has been covered in the session and then to ask students to reflect upon their next steps and what they will take away from the session.

In terms of how long to run a workshop, this will depend on the nature of the topic and whether it is in-person or online. In my practice, both my online and in-person workshops have ranged anywhere from 30 minutes (for more didactic sessions) to up to an hour and a half. You will need to consider how much content there is to cover, whether the content is sufficiently engaging for the amount of time you have to teach, and whether students (and you) will be able to maintain concentration for the time period. You will also need to factor in time for things going wrong with the technology for instance, and for answering questions. It is good to keep in mind that activities may take longer or shorter than planned, therefore always have back-up or extension tasks for students.

Another thing to think about when delivering online (and in-person) workshops is your use of slides or technology. Will you be using presentation software such as PowerPoint? Are you intending to use an interactive whiteboard? Are you intending to use online interactive tools such as Mentimeter or Padlet? Will you be recording the session? If so, make sure you do a run-through of the technology beforehand to counter any potential mishaps. If it’s the first time you have used the technology or software, don’t be afraid to share that with students in the session as they will often be very accommodating. Similarly to the point above, always have a back-up plan for if the technology fails. This can help you feel more at ease and in-control and will prevent panic setting in for when things do (inevitably) go wrong.

How do I find resources for workshops?

You may find in the early days as a learning development tutor that you will need to rely on materials for workshops that aren’t your own and to adapt them to suit the needs of your students. This can help relieve some of the pressure of having to ‘develop’– indeed, your university may have many long-standing resources already available – so do make use of them.

If you are having to start from scratch when making workshop materials, a good place to start is from the ALDinHE Learn Higher site. Learn Higher http://www.learnhigher.ac.uk/ is the go-to site for all things teaching-related in learning development. It is a resource page of peer-reviewed teaching resources that are generally available for free use, download and adaptation. Resources cover a wide range of skills including criticality, research skills and writing for university. I have used and adapted many materials from the site, and it is highly recommended as a starting point for new LDs trying to establish good practice in their teaching. Knowing that these resources have been ‘tried and tested’ by the LD community can also help to ease the worry of whether your workshop material is ‘adequate’.

Other useful starting points for materials are to look at the study skill and learning development resources from other university contexts (just run a ‘Google’ search – we all do it!). My favourites are the York University Skills Guide: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/skills, the UCL Academic Writing Centre, The North Carolina Writing Centre, The Online Writing Lab (OWL) from Purdue University, and Swansea University’s Library referencing guide; but these are just some of many, so enjoy the process of searching and investigating for materials to adapt and use.

If you are using images or resources, check that they have a Creative Commons License which grants individuals permission to use others’ creative work. Also, as we encourage the students, ensure that you acknowledge or reference any material that is not yours.

How do I encourage dialogue and engagement in a workshop?

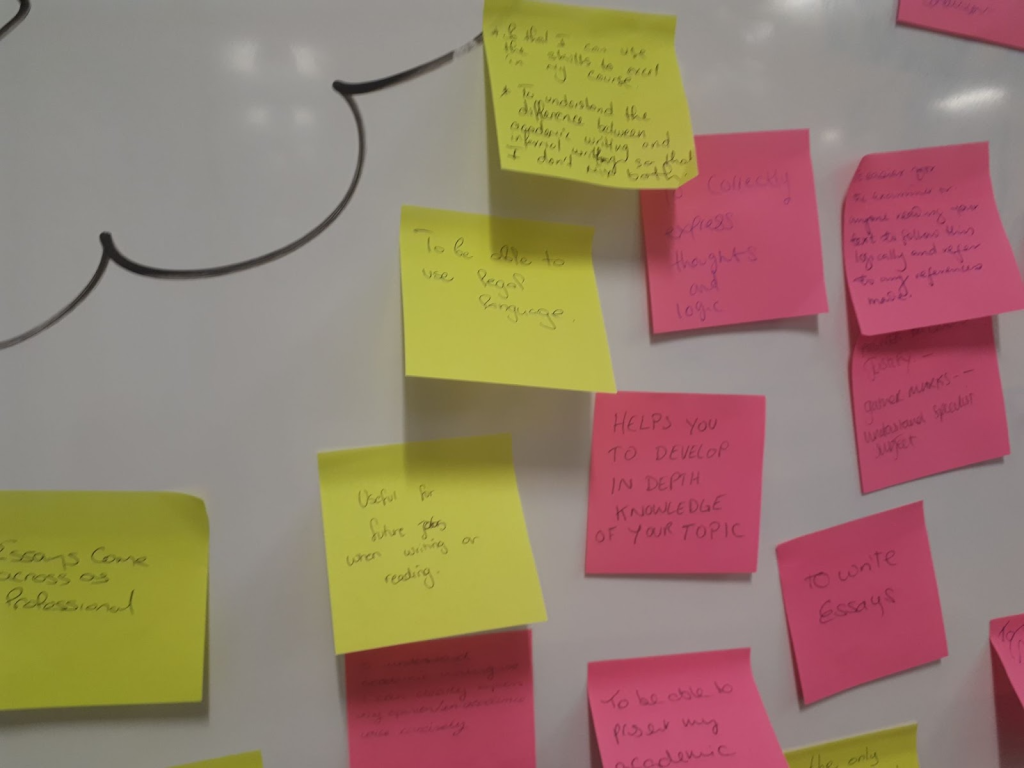

It is important within workshops, to encourage dialogue and engagement amongst student participants and yourself. Remember, dialogue does not necessarily need to be spoken. It is fine to use chat or other interactive tools or, in a classroom situation, to get students to respond in other ways other than speaking (good old-fashioned post-it notes work well). However, you will need to ask questions to encourage dialogue.

Questions can either be closed or open. Closed questions are questions that can be answered with a simple word or short phrase; for example, how many examples of signposting language can you see? Open questions, as the name implies, encourage longer, more detailed responses. For example, you may ask, ‘Can you tell me what you understand by criticality?’ Both closed and open questions have their place in a workshop; but using questioning should encourage the development of critical faculties amongst your students.

Good questioning can come about spontaneously, but in the earlier days as a learning developer, it might be a good idea to plan for the types of questions that you may wish to ask – have a prompt card or notes on your presentation and use these as a guide.

You could also try using concept cartoons for higher-level questioning and thinking. As a teacher, I would often use concept cartoons as a way of encouraging dialogue amongst the students in lessons. Concept cartoons are typically used in science lessons when teaching new scientific concepts. Students are presented with a scenario where various viewpoints are posited. This encourages students to think about which (if any) viewpoint they agree with and leads to further, deeper questioning. As an example:

Image: Cartoon conversation on gravity: From: https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/2566-using-concept-cartoons accessed 30/01/2021.

This idea can be easily adapted for teaching university students across any discipline. Essentially, you present students with a scenario; for example, ‘ideas about critical thinking’ and put a few viewpoints in a concept cartoon format; for example, ‘Critical thinking isn’t important’ ‘Being critical is about criticising’ ‘Critical thinking involves making judgements’ and so forth. Then allow your students to engage in a discussion (perhaps using breakout rooms or in small table groups if they are in a classroom) around the concept.

Another way of encouraging engagement in workshops is to present students with a relatable and relevant scenario and ask them their thoughts or ideas to help resolve the issues presented. I took this idea from Stella Cottrell’s Study Skills Handbook (a brilliant book for those new to learning development and for students), where she presents scenarios to stimulate thought and discussion. For instance, in a workshop on building confidence for online learning, I presented the students with the following scenario based on a fictional student, Jason:

“I have challenges with time management, and I find using the online materials/Moodle confusing. It takes me a long time to work it all out. I’m finding the entire ordeal very stressful, and I feel isolated. I struggle with staying motivated and often spend hours just staring at the screen without doing much.”

I then asked the students to give ‘advice’ to Jason and to discuss this in small groups. From this simple activity, the students came up with a whole host of suggestions and advice for Jason:

- Create a weekly schedule.

- Have to-do lists and prioritise tasks.

- Complete a training session on the Learn Online Moodle course.

- Ask for clarification from a personal tutor.

- Speak to a friend/family member about your experiences.

- Join a WhatsApp group and keep in touch with classmates (they are likely feeling the same).

- Keep in contact with your personal tutor.

- Work little and often.

- Give yourself regular rewards.

- Create a routine/schedule and try to stick to it.

- Remind yourself of the end goal.

Encouraging dialogue in this way opens up opportunities for further debate and discussion, and also gives students a sense of ownership during the session.

Image: Using simple post-it notes to aid with dialogue to promote dialogue in an in-person workshop. This could be easily adapted for online workshops, using tools such as Google Jamboard or Padlet.

How do I respond to questions I don’t know the answer to?

Another thing to consider is that students will ask you questions in workshops and when you start this can be quite a scary concept – asking questions on a range of issues that you may not feel so confident with yet, particularly if you are teaching students from a range of disciplines. However, it can be helpful to remind yourself that you are not in battle with the students; usually, they are on your side, you don’t have to present yourself as the font of all knowledge. They are there to learn, most of them are highly motivated, and your answers to their questions might set them off on the right track. Indeed, not knowing the answers can also prove a useful learning curve for you. I’ve learned a whole host of things because of ‘difficult’ questions as I then later research the point. If you really don’t know then it’s fine to say so, perhaps with the caveat that you will investigate it and try to get back to them at a later stage. And then do follow-up. Or you can also ask the other students in the workshop what they think i.e., ‘That’s a great question, what do others in the room think?’, get them to discuss the question briefly with a partner and then give feedback to the class.

What are tutorials?

Learning development tutorials are usually one-to-one sessions (although they can be groups) held with students to discuss a specific aspect of their academic skills development.

In terms of the optimal time for a tutorial to run this is not set in stone. Indeed, there has been much discussion on the Learning Development Higher Education Network (LDHEN) JiscMail mailing list about the most conducive length of tutorials. Some have argued that tutorials lasting under an hour do not allow enough time to adopt a ‘teaching-centred’ approach and instead end up being quite prescriptive, rather like going for a doctor’s appointment.

In my own experience, I’ve found that anything less than about 30 minutes might be insufficient in terms of enabling students to talk in enough depth about their concerns, and anything over an hour may be draining for both you as the learning developer and the student. Initially, when I started in learning development, my sessions ran for 50 minutes, but over time, I have adjusted these to 40-minute sessions with 20-minute gaps in between tutorials to allow for overrunning if necessary. I offer between 4 to 6 sessions a week. I have found 40 minutes enables students to have enough time to discuss their concerns in enough depth. If time is insufficient, students also know that they can have follow-up sessions if necessary. In addition, you might also trial shorter drop-in sessions (of about 10-20 minutes) where students with ‘quick’ queries on essay writing or referencing, for instance, can get their questions answered.

How can I structure a tutorial?

When I started as a learning development tutor, although I had some experience of teaching tutorials on a pre-sessional course, I lacked confidence in how to run a tutorial effectively. I would panic that I would have little to offer in terms of guidance, teaching and good practice. What I’ve learned is that the most effective tutorials are not a one-way street where I give ‘prescriptive advice’ to the student. Instead, in my experience, the most effective tutorials I have had are where students feel a sense of belonging, of safety to communicate with me, and where some form of teaching and learning takes place. I see my role in tutorials as a critical friend, helping students to navigate the muddy waters of academia, their subject, and academic practices. Below are some practical suggestions and advice I could offer for running effective tutorials.

Prepare beforehand:

This may be more or less difficult depending on if you work for a particular faculty or department, or indeed, work across your institution with students from many different disciplines. In my context, I am based in one faculty, specifically supporting law and criminology students.

As a minimum, I would suggest making sure you are clear on what programme the student is taking, what year they are in, and that you have a round-about idea of what they would like to discuss – but be flexible as often what students think they need to discuss leads to many other questions, so be prepared to go off on a different tangent. It can be helpful to ask students to fill out a short form or pro-forma with this information (or just an email) before they attend the tutorial. It might be helpful to create a template of the key information you need about the student to refer to in your session where needed (see attached example).

Have a list of go-to-resources and guidance:

The more tutorials you experience, the more you will realise that student concerns tend to be quite similar or fall into a pattern. Common areas of concern include essay writing, referencing, time management and organisation, reading and concerns about the course. Try to create a bank of frequently asked questions that may crop up in sessions and some responses or resources as a starting point. For example, questions could include: How do I write an essay? How do I improve my marks? Can you explain how this referencing system works? I’ve failed an assignment – help!

Being aware of some typical concerns or queries that may crop up can alleviate the feeling, as a learning developer, of being in the unknown. However, be ready and be flexible for concerns which you have not thought about to crop up – this is the nature of our work. Indeed, you might find, particularly given the current climate, that students just want to chat or vent about their struggles, so be prepared for this, though remember to have clear boundaries and to signpost students to relevant services (e.g., disability services, counselling, student services) if they need support outside the scope of your role.

Structure the tutorial so that you have an introduction, main body, and conclusion:

I would argue that much like a workshop, tutorials should have a clear structure. That is not to say that you must stick rigidly to the structure, but you should have a clear idea of how to start, what to cover in the main part of the session and how to conclude it. Remember the mantra for structure, ‘This is what we’re going to discuss’, ‘Here we are discussing it’ and ‘This is what we discussed’.

A good way to start a session is to introduce yourself and your remit briefly if you haven’t met the student, ask how the student is, and to ask what they would like to focus on or get out of the session. This can help to establish rapport, boundaries, and expectations.

Listening carefully during the tutorial is important so that you can pick up on areas that perhaps are helpful, but the student doesn’t mention. You may wish to make notes.

In the main part of the tutorial, I would argue that the student should be doing something. Depending on the student’s concern, you could model or scaffold a process for them (e.g., writing a clear topic sentence) and then get them to have a go themselves. You could also look at an extract from their writing and focus on a specific aspect e.g., grammar, language, structure, and talk through their thought processes and areas of concern.

When I first started delivering tutorials, it felt very nerve wracking not being able to ‘plan’ for what the student wanted to discuss. Indeed, often my tutorials ended up being quite generic rather than personalised as I tried to ‘stick to the plan’. However, I have found that with more experience, I am more comfortable allowing the sessions to be ‘led’ by the student, so to speak. That is, I find it helpful to ask guiding questions to explore the students’ concerns and to aid them in thinking about strategies and ideas to assist them. This might take the form of Socratic questioning or a coaching approach.

Ask the right questions:

Adopting a Socratic-style or approach can be helpful when engaging with students in tutorial. Socratic questioning, derived from the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, is an approach that enables questioning and unearthing of underlying values, beliefs, and understandings. It involves a dialogue between you and the student which gives an opportunity to question underlying assumptions, to challenge and to arrive at reasoned understandings; namely, to be critical. Examples of questions you might ask could include:

- Can you tell me more about that?

- What led you to that conclusion?

- Tell me about why you chose that strategy or approach?

- What do you like about your work?

- What puzzles you about the writing process?

That is not to say you should just ask a list of questions without using other forms of dialogue, but it can be a way to begin to engage with students about their underlying understandings and challenges with their learning.

Being human:

It can be helpful to share a little of your own experiences of studying with students (whilst maintaining boundaries and only to the extent that you are comfortable doing so). For instance, if a student is discussing struggling with managing references, I may tell them a short story of my own struggles with finding appropriate sources and struggling with getting to grips with Zotero (reference management software) during my degree.

Sharing little snippets of your own struggles with studying and how you overcame these can help the student to see that you are human and relatable which can be particularly helpful where the student is finding it hard to find connections or a ‘friendly face’ during their time at university.

Be flexible:

It’s important to be led by the student. Often, you will find that students come with a very specific concern e.g., to ask for guidance on how to write a clear essay introduction. But, often, once you begin to unpack this a little bit (perhaps through Socratic questioning) you may find that there are other issues that are crucial to discuss. For instance, often during tutorials students want to discuss how to improve their essay writing skills, but in the process of the tutorial, through questioning, I will come to see that there are many underlying concerns such as issues with time management and procrastination. Knowing how to be flexible regarding tutorials is a real skill and can be one of the most daunting aspects as a new learning development tutor. To aid with this, it can be really helpful, particularly in those early days, to have that bank of resources, guidance and tips that you can refer to, if you need.

Follow up after the session with the student with useful resources.

It can be helpful to follow up with the student(s) after the session with an email providing a list of helpful resources and links that the student can follow up with independently. This can also help the student to take ownership of their own learning. In addition, it can be nice for the student to know they can always contact you again (if services permit) if they want to talk further about an aspect of their studies.

Keep track of who has attended tutorials and consider asking for feedback.

Having a way to monitor or record who has attended tutorials is essential for tracking who is using your services and to aid with providing data for wider institutional concerns such as retention and progression. This data can also be used to inform you of who is accessing and engaging with your services so that these services can be developed and improved.

So, where else can I go for advice or inspiration to help with becoming a better LD?

Another idea is to seek out opportunities for shadowing more experienced colleagues or to seek out a mentor. I found it helpful in my first year to have a mentor at the university who was more experienced than me, but who essentially carried out the same role, albeit non-faculty based. I met with my mentor regularly and had the opportunity to observe their workshops. This enabled me to ask questions about conducting workshops, running tutorials and where to find resources, and was a helpful springboard in starting to develop professionally in my role.

As well as this, seek out opportunities to engage with the learning development community as this will help to build your confidence that you know what LD ‘is’, what its values are, and how colleagues across different institutions are doing the job. For instance, you might consider attending the annual ALDinHE conference, a three-day conference, held at a university in the UK and typically attended by over 150 delegates from across the UK and further. Other options for engagement include joining a learning development working group whether in ALDinHE or in your university context. At my university, we have a team of learning development tutors who work in different faculties who meet regularly in a working group to discuss different aspects and challenges of the role. You might also consider joining the LD community on Twitter with the hashtag #LoveLD. Other ideas include becoming a member of ALDinHE, seeking out a mentor on ALDinHE, or perhaps even contributing to a blog! If you are wanting further practical ideas and inspiration for teaching practice, consider coming along to the LD@3 programme which are hour-long webinars on topics pertinent to LD. I have watched weird and wonderful presentations on memes, using images to teach critical analysis, and the comedy of learning development. I’ve found these sessions helpful for my professional development and have tried out some of the resources and ideas, with mainly positive results, in my own workshops. Engaging with the community like this can be a real confidence boost and you may even find that you surprise yourself that you are already doing a lot of things ‘right’.

Other useful resources that you may find helpful include blogs about learning development from Helen Webster available at: https://rattusscholasticus.wordpress.com/category/ld-values/ or #Take5 – the Learning development blog: https://aldinhe.ac.uk/blog , or the LD podcast which all provide a wealth of useful ideas, activities, and inspiration.

Image: Keynote speech from the first ALDinHE conference I attended, held at the University of Exeter. Attending conferences is a great way to get involved with the LD community.

Final thoughts

In my context, there are only two learning development tutors in our School, although we have other learning development tutors working across different faculties and Schools. I found co-teaching and talking with a more experienced colleague useful in terms of developing my pedagogical approach in those early years in the role. The learning development community is a very supportive one so don’t be afraid to ask questions of colleagues and the wider community.

The intention of this blog was to provide some tips and ideas for those new to learning development. We considered two of the primary-student-facing aspects of the role; namely, tutorials and workshops. We looked at effective ways of conducting workshops and tutorials and considered resources and tools that can support early career learning development tutors with this. It’s important to reiterate the point that whilst this blog might be helpful as a starting point for those new to LD, it is not intended as prescriptive. Given the complex dynamics of our student facing role, and the varied contexts in which we find ourselves working, much of the process will entail learning through practice, experience, and dare I say it, sometimes failure, – therein lies much of the joy and fun of LD. Welcome to the community and I do hope this blog was of some use to you.

Bio/Blurb

I am a Learning Development Tutor within the School of Law at Birkbeck, University of London, a medium-sized, (predominantly) evening university with its main teaching campus in Bloomsbury, London. Birkbeck has a widening participation ethos and many of its students are mature and/or are the first in the family to study at university. I have worked at Birkbeck since 2018, initially part-time and, from 2020, as a full-time tutor, teaching and supporting the academic skills development of undergraduate and postgraduate students undertaking Law or Criminology programmes and modules. I am a qualified teacher, gaining QTS in 2005, and taught in state schools in London and Cambridge for 13 years as well as teaching on pre-sessional EAP courses and EFL in UK-based summer schools. I am a Fellow of Advance HE (FHEA) and have an MEd (Cambridge), PGCE (Southampton), LPC, GDL, BSc, and CELTA qualifications.