Play provides the energy, the eruptions, the poetry and the connectivity for engagement and success. Play transforms deficit-fixing teaching, it is creative and emergent, it provides spaces and places of reimagining and agency – play has the power to transform education, and educational experiences and outcomes (Sinfield et al., 2019).

This #Take5 is brought to you from Sandra Sinfield (London Metropolitan University), Tom Burns (London Metropolitan University) and Sandra Abegglen (University of Calgary). Drawing together playful, arts-based and creative practices, this post offers theoretical arguments for why we all need a more creative Higher Education (HE) to build a more inclusive HE. As well as discussing the theory behind their Facilitating Student Learning (FSL) module, it showcases examples of multimodal artefacts produced by their Managing the Assessment and Feedback Process (MAF) participants – and invites us to share our creative teaching, learning and assessment practices.

For more information on using collage and visual practices in the classroom, do see:

Abegglen, Burns & Sinfield (2020). Montage, DaDa and the Dalek: The Game of Meaning in Higher Education. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 2020, Vol. 7, No.3. ISSN 2056-757X https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.73.20-016 .

Introduction: Creative Practices in Teaching, Learning and Assessment

Art has begun to feel not like a respite or an escape, but a formidable tool for gaining perspective on what are increasingly troubled times (Laing, 2020).

Playful and creative learning and teaching approaches have found their way into HE classrooms (James & Neranzti, 2019; Nerantzi, 2016), not as ‘dumbed down’ teaching but to provoke the ‘serious business’ of real, engaged and authentic learning (Parr, 2014; Sinfield, Burns & Abegglen, 2019; Abegglen, Burns & Sinfield, 2018; Burns, Sinfield & Abegglen, 2018). Play gives students the freedom (Huizinga, 1949) to experiment, to question, to engage – and to accept uncertainty. This is important in these supercomplex (Abegglen, Burns, Maier & Sinfield, 2020a), lean and mean times (Giroux, 2014) where the present is uncertain and the future even more so. The teaching and learning of supposedly fixed ‘forms of knowledge’ (Hirst, 1974) and the developing of ‘traditional’ skills are no longer sufficient – if they ever were. What is needed are methods that enable students to evolve and transform as they co-construct their knowledge in ludic ways (Sinfield, Burns & Abegglen, 2019) – an epistemological shift, the bringing together of theory and practice (Bernstein, 2001) in active, creative learning. For it is in play and only in playing that the individual is fiercely alive, able to use the whole personality, creatively (Winnicott, 1971). It is a medium for developing – and growing.

The majority of our University’s students do not enter with solid educational foundations – and thus our task as staff – and as staff developers – is to make sure that they are not disadvantaged by this. Typically, we harness creative, arts-based and ludic practice to destabilise that very unequal education system that has positioned them as outsiders. We de-school (Illich, 1972) and un-school (Holt, 1976) staff and students, so that together they can critique and interrogate the system that they are entering and create their own selves as they become academic on their own terms. It is why we incorporate creativity and playfulness into our teaching and learning practice, especially in our FSL module, the first module in the Postgraduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (PGCert) course and the Masters in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (MALTHE) programme at London Metropolitan University (UK).

In this blogpost we discuss the power of creativity drawing on the case of our own FSL module. We also spotlight the potential of creative assessments by weaving in some of the multimodal group presentations that participants on our MAF module have produced. Our provocation: please share your own creative practices with us and the wider community – by email or on Twitter using the hashtags #LoveLD and #creativeHE.

Facilitating Student Learning: Visualising the University

…the image possesses an uncanny power. It can travel where the body can’t. It migrates and strays, taking up permanent residence in the mind, revealing what – who – has been forcibly excluded from sight (Laing, 2020).

In FSL, we use creative and ludic practices to deepen the learning experiences of our staff learners, to make space for them to think, see and be, differently – and to increase the repertoire of creative learning, teaching and assessment strategies that they can utilise in their own practices. Typically, all our FSL participants have multiple responsibilities and, like their students, they are time poor and under constant pressure – but they are willing to explore their practice through the dialogic space that our module creates. We aim to “make strange” (Shklovsky, 1990) taken-for-granted notions of education; to move to a place of “safe uncertainty” (Mason, 1993) – using playful exploration and collaboration as a catalyst for creativity. We want our participants to engage critically, mindfully and reflectively with our module – using it as a lens to interrogate their own ways of ‘doing’.

Thus a key aspect of our FSL module is that we ‘immerse’ participants in playful and creative learning; we facilitate an opening up and an imagining of what they, the education system and their students could be (see also McIntosh, 2010; McIntosh, 2007). The FSL module harnesses collage, making, drawing, poetry, role play, discussion, bricolage, image-, topic- and scenario-mediated dialogue – to explore education praxes and to reimagine education more inclusively and powerfully. We incorporate reflective practice (Schön, 1983) and reflective writing (Elbow 1998) as our staff-as-students develop new ways of developing their emergent teaching and assessment practices. All our staff learners are encouraged to keep and share their own learning logs, blogs and padlets to engage with their own learning and teaching practice and with that of their peers. These opportunities for dialogic reflection and meta-reflection are part of the participants’ professional development as they take ownership of who they are, what they know and the practical and theoretical perspectives they are encountering.

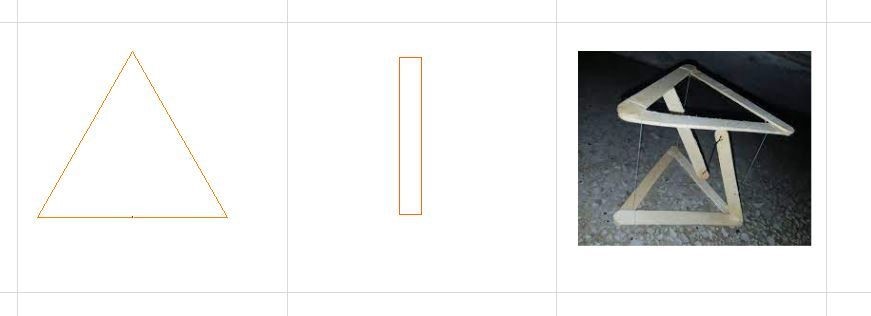

Every year as part of the FSL curriculum, we ask staff to create collages of themselves as academics, to visualise or ‘make’ students – and to create representations of the university itself (see MoMA, n.d.). These creative artefacts enable powerful discussions of the what, why and how of teaching, learning and assessment – and of how to create a humane university. In the process, we place a strong emphasis on developing the ‘self’, as ‘knowing’ oneself is a key attribute for being able to develop (Rogers, 1961) and to move on to the precarious ground of teaching – and of developing education for social justice. Each year they build more optimistic representations of HE; porous and amorphous structures with flexible and welcoming learning and teaching spaces and assessment practices that acknowledge and accommodate the people that enter. These model Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) represent open universities that allow a weaving in and out of diverse people and ideas. At the end of FSL, together we have creatively brought into view new visions of the teaching self, the student self and the institutional ‘self’ – and have explored how we might make HE a better fit for the human beings that university is ostensibly designed to accommodate: through playful practice we have modelled a humane education (Abegglen, Burns, Maier & Sinfield, 2020b).

Image: Representation of HE – FSL Participant, 2023

Assessing – more creatively

FSL is assessed by portfolio – and the constituent parts are developed over time and deepened by peer review processes. The final element is a meta-reflection – and our staff-as-students are invited to write a formal essay if they wish – or to develop a reflection in a mode of their own choosing. We have been fascinated and delighted by Vlogs and video essays, by animations and fairy tales – and most recently by staff who collaborated to produce a children’s book harnessing the creative and liberatory practices of the module itself. These assignments give us hope which”‘is the precursor to change. Without it, no better world is possible” (Laing, 2020).

Image: Representation of HE – FSL Participant, 2023

We are all post-digital now

Of course everybody was abuzz with thoughts about ChatGPT – ranging from “It is the end of days!” to approaches that are more positive: “We’ll have to design creative assessments.” It is clear that we have to experiment and play with ChatGPT and all the other AI tools to discover how best to teach with and about them. We hope that ChatGPT might be folded into novel and provocative ‘write to learn’ approaches in the classroom and a re-thinking of assessment that ushers in a more creative and multimodal approach. As said, we offer a choice of assessment format in our FSL module – and in our MAF module. For example, we swapped a 15-minute F2F group presentation with a five-minute multimodal artefact. Our hope here was that staff would explore alternative and perhaps more creative assessments in an embodied way – and thus feel secure when offering them to their students.

Video: MAF artefact – assessment for and as learning

Video: MAF artefact – who are the disadvantaged in assessment?

Conclusion: The Thing Itself Always Escapes?

Art is a place … where ideas and people are made welcome. It’s a zone of enchantment as well as resistance, and it’s open even now (Laing, 2020).

There are many reasons to start our PGCert course and FSL and MAF modules in the way that we do. One is our belief in creativity as liberatory and reparative practice (Sedgwick in Laing, 2020; Sinfield, Burns & Abegglen, 2019) coupled with our perception that typically the pre-tertiary education system with its transactional focus on League Table positions and consequent urge to ‘teach to the test’ will have worked very successfully to eradicate the creative in most learners (see also Ken Robinson, TED talk, 2006) – and thus damage their self-efficacy and sense of self. Working in a predominately widening participation HEI we see students arrive with little self-belief. ‘Nontraditional’ students in particular are made to feel unwelcome or uncomfortable within HE, where a typical response is to see them as ‘deficit’ and to devise supplementary programmes or instruction to ‘fix’ them (Sinfield, Burns & Abegglen, 2019). Rather than accept this reductive and ‘colonising’ vision, we develop with our staff creative and liberatory courses of transformation. Ludic, open and creative activities that make transparent the forms and processes of academia and create spaces that allow: “a feeling of being inducted back into hope, a restoration of faith” (Laing, 2020).

With the rush to make HE – and academic staff themselves – more agile, efficient and accountable, a concept is emerging of an also deficit staff that needs ‘fixing’ or at least micro-managing (Sinfield, Burns & Holley, 2004). We do not conceive of our modules as a way of ‘fixing’ staff – nor of preparing them to ‘fix’ their students. Rather we use creative and ludic practices as a way of helping them explore more ‘ways of seeing’ (Berger, 1972) the educational context(s) in which we all operate. Being enabled to see and think differently “can be a route to clarity … a force of resistance and repair, providing new registers, new languages in which to think” (Laing, 2020). Our practices allow the surfacing and discussing of the problematic nature of HE itself, of the systemic inequities built into the very systems with which our staff and students have to engage. What we attempt is creative action and reflection – opportunities for our participants to actively and critically engage and thus to develop curricula and pedagogic practice that better help them and their students to become their whole creative selves. Our staff learners acknowledge HE systems that foster power and pain – but in their own practice they build opportunities for creativity, porosity and openness: a new vision of what education could be. Their work constitutes acts of hope and of resistance.

Image: Representation of HE: FSL Participant, 2023.

Ways to get involved with:

- #101 Creative Ideas: https://101creativeideas.wordpress.com/category/creative-ideas/

- Creative Academic: https://www.creativeacademic.uk/

- CreativeHE Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/262933554606607

- CreativeHE Community: https://creativehecommunity.wordpress.com/

- #Take5: Write your practice? Email: s.sinfield@londonmet.ac.uk & t.burns@londonmet.ac.uk with your blog ideas.

References

Abegglen, S., Burns, T., Maier, S. & Sinfield, S. (2020a), “Supercomplexity: Acknowledging students’ lives in the 21st century university”, Innovative Practice in Higher Education, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 20-38.

Abegglen, S., Burns, T., Maier, S. & Sinfield, S. (2020b), “Global university, local issues: Taking a creative and humane approach to learning and teaching”, in: Blessinger, P. (eds.), International perspectives on improving classroom engagement and international development programs: Humanising higher education, (Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, Vol. 27), Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 75-91. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2055-364120200000027007

Abegglen, S., Burns, T. & Sinfield, S. (2018), “Drawing as a way of knowing: Visual practices as the route to becoming academic”, Canadian Journal for Studies in Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, 28, pp. 173-185. https://doi.org/10.31468/cjsdwr.600

Bateson G. (2000), Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226924601.001.0001

Berger, J. (1972), Ways of seeing, London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Bernstein, B. (2001), ‘From pedagogies to knowledges’, In: A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies, and H. Daniels (eds). Towards a sociology of pedagogy. The contribution of Basil Bernstein to research, New York: Peter Lang, pp. 363-368.

Burns, T., Sinfield, S. & Abegglen, S. (2018), “Re-genring academic writing”, Journal of Writing in Creative Practice, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 181-303.

Elbow, P. (1998), Writing without teachers, 2nd Edition, New York: Oxford University Press.

10. Giroux, H. A. (2014), Neoliberalism’s war on higher education, Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Hirst, P. H. (1974), Knowledge and the curriculum: A collection of philosophical papers, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Holt, J. (1976), Instead of education, Harmondsworth: Pelican.

Huizinga, J. (1949), Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Illich, I. (1972), Deschooling society, New York: Harper and Row.

James, A. & Nerantzi, C. (2019), The power of play in higher education: Creativity in tertiary learning, London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95780-7

Kay, J. and King, M. (2020), Radical uncertainty: Decision-making beyond the numbers, New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Laing, O. (2020), “Feeling overwhelmed? How art can help in an emergency”, The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/21/feeling-overwhelmed-how-artcan-help-in-an-emergency-by-olivia-laing [Accessed 23 April 2020].

Mason, B. (1993), “Towards positions of safe uncertainty”, Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, Vol. 4, No. 3-4, pp. 189-200.

McIntosh, P. (2010), Action research and reflective practice: Creative and visual methods to facilitate reflection and learning, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203860113

McIntosh, P. (2007), “Reflective reproduction: A figurative approach to reflecting in, on, and about action”, Educational Action Research, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 125- 143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790701833162

Moen, T. (2006), “Reflections on the narrative research approach”, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, Vol. 5, No. 4. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F160940690600500405

MoMA (no year), “Dada: Discover how dada artists used chance, collaboration, and language as a catalyst for creativity”, MoMA Learning. Available from: https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/dada/chance-creations-collage-photomontage-and-assemblage/ [Accessed 15.05.23].

Nerantzi, C. (2016), “Learning to play, playing to learn: The rise of playful learning in higher education”, in: Digifest 2016. Available from: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/news/learning-to-play-playing-to-learn-the-rise-of-playfullearning-in-he-25-feb-2016-inform [Accessed 20 February 2020].

24. Parr, R. (2014), “The importance of play”, Times Higher Education, Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/the-importance-ofplay/2012937.article [Accessed 20 February 2020].

Robinson, K. (2006), “Do schools kills creativity?”, TED talk, Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity?language=en [Accessed 23 April 2020].

Rogers, C. (1961), On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy, London: Constable.

Schön, D. A. (1983), The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, London: Basic Books.

Shklovsky, V. (2015, translated by Alexandra Berlina), “Art, as device”, Poetics Today, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 151-174. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-3160709

Shklovsky, V. (1990), “Art as device”, In: V. Shklovsky (translated by Benjamin Sher), Theory of prose, Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, pp. 1-14.

Sinfield, S., Burns, T. & Abegglen, S. (2019). “Exploration: Becoming playful – the power of a ludic module”, In: A. James and C. Nerantzi (eds.), The power of play in higher education: Creativity in tertiary learning, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95780-7_2

Sinfield S.; Burns, T. & Holley, D. (2004), “Outsiders looking in or insiders looking out? Widening participation in a post-1992 university”, In: J. Satterthwaite, E. Atkinson, W. Martin (eds.), The disciplining of education: New languages of power and resistance, Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books, pp. 137-152. 33. Winnicott, D. W. (1971), Playing and reality, London: Tavistock.

Bios:

Sinfield, Sandra is a Senior Lecturer in Education and Learning Development in the Centre for Professional and Educational Development at London Metropolitan University and a co-founder of the Association for Learning Development in Higher Education (ALDinHE). She has co-authored Teaching, Learning and Study Skills: A Guide for Tutors and Essential Study Skills: The complete Guide to Success at University (5th Edition). Sandra is interested in creativity as liberatory and holistic practice in Higher Education; she has developed theatre and film in unusual places – and inhabited SecondLife as a learning space.

Burns, Tom is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Professional and Educational Development at London Metropolitan University, developing innovations with a special focus on praxes that ignites student curiosity, and develop power and voice. Always interested in theatre and the arts, and their role in teaching and learning, Tom has set up adventure playgrounds, community events and festivals for his local community, and feeds arts-based practice into his learning, teaching and assessment practices. He is co-author of Teaching, Learning and Study Skills: A Guide for Tutors and Essential Study Skills: The Complete Guide to Success at University (5th Edition).

Abegglen, Sandra is a Researcher in the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at the University of Calgary where she explores online education, and learning and teaching in the design studio. Sandra has a MSc in Social Research and a MA in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. She has extensive experience both as a social researcher and lecturer/programme leader. She has published widely on emancipatory learning and teaching practice, creative and playful pedagogy, and remote education. She has been awarded for her inter-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder education work.