By Dr Selen Kars-Unluoglu (University of the West of England) & Prof Burcu Guneri-Cangarli (Izmir University of Economics)

Arts-based methods which traditionally rely on engagement with material artefacts (e.g. LEGO® bricks, finger puppets, craft materials) have been on the rise in management learning and teaching (Taylor and Ladkin, 2009). COVID-19 has challenged educators to adapt these methods to online teaching environments. The challenge was to get learners to move from thinking to thinging (Knappett & Malafouris, 2008)in online environments without the opportunity to pass on, share, co-engage with material artefacts in a physical setting.

While there has been some discussion in the field about ways of adapting these methods to online environments and the impact this has on learner outcomes, there has been no discussion about experiences of educators. Yet, we know that technology in universities “disfigures academics’ work and identity” (McWilliam, 2004: 89). Instead, the silence persists around how our practices and sense self are shifting – refigured as much as this figured – as we move arts-based teaching into online spaces.

In the wake of this silence, we wanted to understand how are educators experiencing this shift in their practices of arts-based teaching? What are they feeling? How are they coping? These are some of the questions we are as part of our research project funded by ALDinHE Small Research Grants that intends to explore the lived experiences of arts-based teaching and learning from an educators’ perspective, and the role of HE institutions in helping educators thrive in the future of online teaching environments.

We have interviewed 13 educators who are using arts-based methods regularly in their teaching practice. We have asked them to write a fictional story that capture their experiences of using these methods in online interviews and enrich their stories with photographs / images. We then have conducted in-depth story and photo elicitation interviews to understand more about their lived experience through the symbols and metaphors offered in the stories and photographs. We have supplemented this by non-participant observation of 9 workshops delivered by these educators where they used arts-based methods.

These stories and images that go with them have revealed some interesting interpretations:

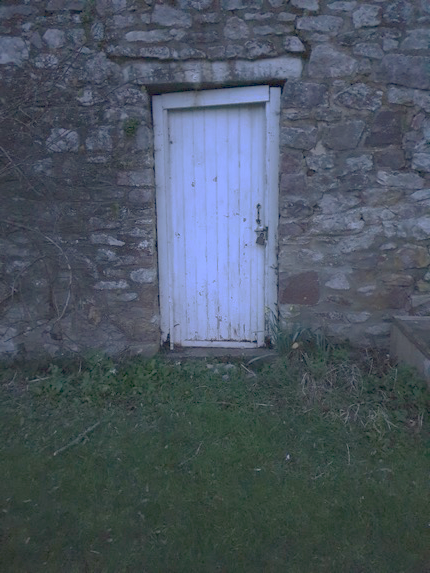

- We have seen that the shift in practices is accompanied by a sense of ambivalence. On the one hand, educators likened the process of integrating the digital into arts-based teaching and learning to an exploratory journey into a “different universe”, “different planet” to “see different creatures”, “smell different flowers”. On the other hand, this journey was always accompanied by a deep sense of jeopardy. Having to translate arts-based teaching practice to online environments was like opening a grotty garden door that “looked rusty, and nasty, and it looks like there should be something really intimidating behind it.”

- The sense of jeopardyemanates from a sense of inefficacy – in terms of technological competency, as well as knowledge of online pedagogies and facilitation of arts-based methods. The educators we interviewed felt quite strongly that all their expertise had been stripped away and they lacked confidence in their ability to rebuild that expertise through working with the technology. Having to think about how to run a specific activity online, to figure about technical side of things, to problem-solve adds another layer of risk to arts-based facilitation – in their words they are “having to figure out the technology in order to be able to do your job”. They recognised that skilful facilitation requires competency development, which they did not have time to acquire. They were worried about “looking stupid, like I didn’t know what I was doing”.

- The existence of a community of practice was crucial in coping with this sense of jeopardy. Some educators expressed feeling lonely and unsupported by like-minded educators. This also fed their sense of self-doubt and inefficacy. Being part of a community, which offers a platform to hear other people’s approaches and to get the opportunity to talk through their practices was perceived as an enabler, and also a way to (rebuild) sense of confidence in one’s own practices.

- There is a tension between trying to make the teaching as inclusive, participatory, and accessible as possible, and recognising that genuine participation can only be possible when there are rich social connections and interactions between learners. On the one hand, educators liked that online spaces are egalitarian since “all of us are divided up in equal size rectangles”. They also perceived them as an enabler of psychological safety as learners “join the class from a place where they feel safe”. However, to ask learners undertake arts-based activities and for them to build the rapport that is necessary for knowledge co-creation requires serious considerations about the relationship and trust (Coad, 2007). Learners can feel “naked” when probing into their arts-based activities. This is where their transformative potential lies. However, it is the ability of the educator to intervene, to clear up the confusion or build safety, is necessary to contain the negative emotions and release the transformational learning. With respect to this, the educators’ ability to intervene is severely limited in online environments. Not being able to see the whole person, or not being able to see the person at all (!) because their camera is switched off or because they are in a breakout room makes timely interventions difficult, if not impossible. Educators mentioned the advantage of being able to ‘read the room’ in face-to-face environments. They talked about the significance of “being eyes to eyes” and the micro moments of blank stares, the fidgety fingers, the tussle and hassle with the materials, the giggles, the change in breathing, the posture, the phone-checking; and how they could catch and clock in these moments during their face-to-face delivery which they then could react to. They also reflected on how it would have been helpful to be able to have a cup of coffee with the learners during a break or to have a corridor conversation privately and separately in clearing up the learner’s concerns and reengage them with the activities. The physical is needed to tell how far they can push the learners and to judge if they are going into a potentially sensitive area, and to allow to bring the learners back in.

Our research suggests the need to alleviate some of the commonly reported sense of jeopardy, and lack of self-efficacy and self-confidence. This requires investment, in terms of time and resources, to professional development in online, arts-based pedagogies. This will improve experiences for educators and, consequently, students. Notably, all participants were experienced educators, who have also been using online platforms for 12-18 months when we interviewed them. However, this expertise did not necessarily reduce or change the sense of disturbance or emotional burdens. One suggestion is to enhance the social connection between educators, by facilitating and setting-up communities of practice at departmental and institutional level. The same applies to learners as well. Creating virtual social spaces that learners can engage beyond the regimented environments of online classes will improve learner experiences within and outside the class, and the effectiveness of arts-based methods in the classroom environment. Perhaps, traditional VLEs are constraining in this sense, and institutions may explore opportunities for facilitating online teaching on platforms originally designed for conferences and virtual fairs, like Gather and Online Town which are centred around fully customisable spaces and makes spending time with communities easier.

If you want to hear more about our research and want to discuss it with us and others, we will be presenting our research at ALDCon22 online, on 10th June 2022. Come and join us!